Partway through Deborah Harkness’ A Discovery of Witches, scholar-turned-witch Diana Bishop encounters a trio of familiar figures: a maiden, a mother, and a crone. These three archetypes are the aspects of the goddess Hecate, appearing as sisters. This triad has resurfaced in everything from Discworld to A Song of Ice and Fire, representing both one woman going through different phases of life and a functional coven of witches, each bringing a different perspective to the magic.

The Hecate Sisters are a useful lens through which to examine the current state of witches in literature—modern takes on a timeless figure, with witches’ conflicts and wants changing with the generations. In A Discovery of Witches, Diana Bishop recognizes that she, with her ability to give supernatural life through her blood, represents the mother figure. Katherine van Wyler, the ancient witch holding a town captive in Thomas Olde Heuvelt’s HEX, met her supernatural fate when her children were taken from her. And while she doesn’t have any children, Patience Gideon is undoubtedly maternal, taking care of the locals of Edda’s Meadow with her herbal remedies—and much more powerful cures—in Angela Slatter’s Of Sorrow and Such.

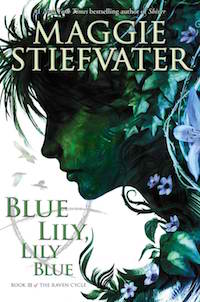

In the past few years, the young adult genre has made renewed explorations into witch stories, tapping into themes of feeling set apart from other adolescents as well as growing into your powers. It’s no surprise, then, that Blue Sargent (Maggie Stiefvater’s The Raven Boys and the entire Raven Cycle) and Nathan Byrn (Sally Green’s Half Bad) stand in for the maiden—who is also depicted as a huntress, which more matches Nathan’s place in his magical society.

The crone, in this case, is Judith Mawson, the old crank from Paul Cornell’s Witches of Lychford—the kind of community elder whose warnings the townspeople shrug off, while still keeping one ear cocked because she’s clearly lived a lot longer than anyone else. One can split the witches (or witches in training) of the past few years generationally, between the old hats who don’t quite belong to this time and the young upstarts who reject their magical heritage but find themselves forcibly drawn in by ancient artifacts and quests with world-ending stakes.

This article discusses plot details of the aforementioned books/series.

The Older Generation: Set in Their Ways

Lychford‘s Judith, Sorrow‘s Patience, and especially HEX‘s Katherine—the women who have cured and chilled their neighbors in equal measure—couldn’t hide their true nature even if they wanted to. These witches are part of their neighbors’ daily lives, but they don’t quite fit. And as much as their respective towns try to move forward in time, these women are a constant reminder of the past.

Still wearing the period clothing and rusty chains in which she was executed, Katherine literally bumps up against modern conventions: She treads the same path she has for three hundred years, even if it leads her into the path of cars, bedrooms, or even lampposts shifted slightly in a prank to test her ability to course-correct. (Spoiler: She can’t. Or won’t.) Katherine’s every move is tracked by Black Spring’s residents through HEX, an app to report Katherine’s latest sighting, so that everyone can know where the witch is at all times. Of course, the app is just one tool belonging to the larger HEX, a Big Brother-like institution that keeps not just Katherine but all of Black Spring’s residents under constant surveillance.

Still wearing the period clothing and rusty chains in which she was executed, Katherine literally bumps up against modern conventions: She treads the same path she has for three hundred years, even if it leads her into the path of cars, bedrooms, or even lampposts shifted slightly in a prank to test her ability to course-correct. (Spoiler: She can’t. Or won’t.) Katherine’s every move is tracked by Black Spring’s residents through HEX, an app to report Katherine’s latest sighting, so that everyone can know where the witch is at all times. Of course, the app is just one tool belonging to the larger HEX, a Big Brother-like institution that keeps not just Katherine but all of Black Spring’s residents under constant surveillance.

Witches’ whereabouts are always recorded—whether literally through a GPS-based app, or by equally eagle-eyed town gossip. After all, people wouldn’t want a witch to take them by surprise.

This witch commands a position of power and fear in her hometown, typically a small village close enough to some eerie woods for strange happenings to touch the fringes of the town. She practices rituals—making medicines, taking offerings—that in another setting would have been erased by modern technology or other innovations. She has not adapted to the times. Often, she keeps her town from fully entering the 21st century, too. With her power to regenerate limbs out of clay and grave dust, Patience can perform the kinds of medical miracles that the encroaching (male) doctors, with their pills and modern science, are nonetheless powerless to compete with. While most of the sleepy hamlet of Lychford prepares for the building of a supermarket, Judith knows what disaster will be brought upon them if the woods are bulldozed—but to everyone else, she looks like the grumpy old lady who can’t handle change. And Katherine not only keeps Black Spring’s residents enraptured with her appearances, but they are tied to her by a curse: If they leave Black Spring for more than a few days, they are seized with horrible thoughts of suicide that will subside only when they reenter the town borders. Black Spring’s fancy HEX app is an unsatisfying trade for the deadly 16th-century heirloom it can’t get rid of.

This witch commands a position of power and fear in her hometown, typically a small village close enough to some eerie woods for strange happenings to touch the fringes of the town. She practices rituals—making medicines, taking offerings—that in another setting would have been erased by modern technology or other innovations. She has not adapted to the times. Often, she keeps her town from fully entering the 21st century, too. With her power to regenerate limbs out of clay and grave dust, Patience can perform the kinds of medical miracles that the encroaching (male) doctors, with their pills and modern science, are nonetheless powerless to compete with. While most of the sleepy hamlet of Lychford prepares for the building of a supermarket, Judith knows what disaster will be brought upon them if the woods are bulldozed—but to everyone else, she looks like the grumpy old lady who can’t handle change. And Katherine not only keeps Black Spring’s residents enraptured with her appearances, but they are tied to her by a curse: If they leave Black Spring for more than a few days, they are seized with horrible thoughts of suicide that will subside only when they reenter the town borders. Black Spring’s fancy HEX app is an unsatisfying trade for the deadly 16th-century heirloom it can’t get rid of.

And yet, these women don’t seek out trouble. Even eerie Katherine, standing over Black Spring residents’ beds with whispers seeping out of the fraying threads of her sewn-shut mouth, is just going about her normal rituals. It’s when the outside world begins to press in too tightly, to take too close a look at the bizarre workings of these towns, that the witches defend their homes.

The Younger Generation: Legacy and MacGuffins

Unlike the older witches operating alone, the younger generation is more concerned with legacy—the future of a witchy family as a power or artifact is passed down, or the outcome of a war between good and evil in the supernatural community. This manifests as White witches pitting their magic against Black witches; witches in a race war with vampires and daemons; or the machinations of a single clan determining its own future. Often these dovetail, like when a young witch’s parents are murdered (in Diana’s case in Discovery) or mortal enemies (like Nathan’s star-crossed folks in Half Bad) in order to get to the offspring with the unprecedented powers.

But unlike the older witches, who inhabit their spaces as supernatural beings, these especially gifted descendants are not necessarily interested in carrying on the (good or evil) family tradition. Like Diana, who has managed to make it all the way to tenure without anyone connecting her surname to Bridget Bishop, the Salem witch trials’ first casualty. Even as magic buzzes in her hands, she stubbornly keeps her focus in science rather than magic.

But unlike the older witches, who inhabit their spaces as supernatural beings, these especially gifted descendants are not necessarily interested in carrying on the (good or evil) family tradition. Like Diana, who has managed to make it all the way to tenure without anyone connecting her surname to Bridget Bishop, the Salem witch trials’ first casualty. Even as magic buzzes in her hands, she stubbornly keeps her focus in science rather than magic.

Despite their best efforts, the fight eventually comes to the young’uns… usually in the form of a good ol’ fashioned MacGuffin. It’s not that Diana intentionally checks Ashmole 782 out from the library knowing it’s a sought-after work of the supernatural; she has a purely academic interest in this alchemical text, nothing witchy. It’s only when the book begins responding to her magic—and reveals its hidden text to her—that Diana realizes her misstep. And even though she immediately shelves it in a panic, it’s too late: Ashmole 782 has revealed itself to her and no one else, which means now the vampires and daemons she avoided are now after her—while she is chasing down the missing three pages from Ashmole 782.

Speaking of threes… Nathan is another reluctant witch who has less of a choice in whether to reject his heritage. As a “half code,” the son of a White witch who killed herself and the most brutal, violent Black witch (think Voldemort but with the added bonus of eating his victims), Nathan already feels unwelcome in the magical world. The White witches Council treats him like he may as well be full-Black, forcing him to report any conversations (no matter how banal) with White witches and to request permission to travel to White territories—which strains his relationship with both his Gran and his half-brother Arran. Soon, he’s not just under house arrest, but actually caged as a ruse to draw out his villainous father, Marcus.

Speaking of threes… Nathan is another reluctant witch who has less of a choice in whether to reject his heritage. As a “half code,” the son of a White witch who killed herself and the most brutal, violent Black witch (think Voldemort but with the added bonus of eating his victims), Nathan already feels unwelcome in the magical world. The White witches Council treats him like he may as well be full-Black, forcing him to report any conversations (no matter how banal) with White witches and to request permission to travel to White territories—which strains his relationship with both his Gran and his half-brother Arran. Soon, he’s not just under house arrest, but actually caged as a ruse to draw out his villainous father, Marcus.

But herein lies the rub: All witches must, by their 17th birthdays, receive three gifts from a witch of their bloodline—one of which includes drinking said family member’s blood. If they fail to obtain the three gifts, they will die. So, Nathan may not want to be the tug-of-war prize between the Black and the White, but he also has his own hide to think about, and a triad of MacGuffins to track down.

For some witches, it’s not so much rejecting destiny outright than assuming that there’s not a place for them in the grand narrative. As the only non-psychic in a house of psychics, Blue Sargent automatically assumes that she’ll be relegated to the proverbial sidelines in all magical matters. But in Blue Lily, Lily Blue (the third book of The Raven Cycle), she discovers that it’s not that she lacks magic, it’s that she’s a mirror:

For some witches, it’s not so much rejecting destiny outright than assuming that there’s not a place for them in the grand narrative. As the only non-psychic in a house of psychics, Blue Sargent automatically assumes that she’ll be relegated to the proverbial sidelines in all magical matters. But in Blue Lily, Lily Blue (the third book of The Raven Cycle), she discovers that it’s not that she lacks magic, it’s that she’s a mirror:

Something prickled in Blue, uncomfortably. She eyed the mirrors; Neeve had used them for divination, Calla said. She’d stood between them and seen endless possibilities for herself stretched out on either side, in either mirror.

Maura was always shuffling the page of cups out of her tarot deck and showing it to Blue: Look, it’s you! Look at all the potential she holds!

“Yes,” Gwenllian said, shrill. “You’re getting it. Do they use you, blue lily? Do they ask you to hold their hands so they can better see their future? Do you make them see the dead? Do you get sent from the room when things get too loud for them?”

Blue nodded dumbly.

“Mirrors,” Gwenllian cooed. “That is what we are. When you hold a candle in front of a glass, doesn’t it make the room twice as bright? So do we, blue lily, lily blue.”

Not only does Blue amplify other witches’ magic, but she also reflects the best parts of the Raven Boys, the other members of her her tight-knit fivesome. But sometimes, instead of those endless possibilities, a reflection gets overtaken by an entirely different image.

Both: Blank Slates

And here is where our two generations of witches, despite their differences in ideology and action, have something in common: They are all blank slates onto which humans (neighbors and readers and writers) project their abject fears and dark desires, their prejudices and biases. Case in point—the mother/maiden/crone construct. Despite their vastly different settings and conflicts, the six witches in these books all slot into that archetype in some way, often negatively so. HEX‘s Katherine is a failed mother because of losing one child to disease and the other after the residents of Black Spring executed her; Half Bad‘s Nathan is a cursed child born of an unholy union, assumed to inherit the worst of his father instead of being able to choose his mother’s path; Lychford‘s Judith must be protesting the supermarket because she hates change, not out of protection for the people of Lychford. Rather than study these living pieces of history and/or their descendants whose magic and attitudes are evolving with time, those without magic ward them off with the evil eye—too frightened of the archetypal villains of campfire tales to consider these women (and men) as flesh-and-blood instead of stories. When it comes to witches, humans are the ones with the evil eye.

These authors must have understood that readers would approach their books with the same assumptions, trying to slot the characters into one of three archetypes. Instead, by having Judith raise her voice at a vital town meeting, Nathan forge a path that belongs to neither of his parents, Sorrow‘s Patience take care of herself instead of others, Blue embrace her identity as a mirror by the end of The Raven Cycle, Discovery‘s Diana embracing both life and destruction… these witches all break the mold.